20th Annual Sierra Challenge, Ten Peaks in Ten Days

20th Annual Sierra Challenge, Ten Peaks in Ten Days

By: Bob Burd

Volcanic Ridge East — Peak 10,213ft

Fri, Aug 7, 2020

Day 1 of the Sierra Challenge

The 20th edition of the Sierra Challenge was ready to begin. It was going to be unusual in its entirety thanks to COVID and the adjustments necessary to do this safely, or at least not unsafely. Luckily, outdoor events have been shown to be far less problematic than indoor ones, but that didn’t mean we had nothing to worry about it. Added precautions included canceling our cook-off, no group photos at start, no large group starts, and the usual mask/social distancing guidelines. For the most part this worked pretty well, but we had our lapses. I was unsuccessful in getting folks to alter their start times to help spread us out – we’re social creatures and most folks wanted to start at the designated time with everyone else. On the trail, I would put on my mask when we passed other groups since it wasn’t always possible to get six feet away, but this was no adhered to universally. Overall, I’d say we did as well or better than the other trail users we came across, and since I had no desire to actually police our COVID policies, I’ll take that as a win.

Today’s goal was on the easy side, about six miles each way with 3,500ft of gain. Volcanic Ridge separates the Shadow Creek and Minaret Creek drainages, found east of the Minarets and the Ritter Range. We had been to the western summit during the 2010 Challenge and I probably should have done the east summit at the same time, but was discouraged by the large drop between them. And though they’re little more than a mile apart, others today would find that doing both together was not trivial. The parking lot at Agnew Meadows was filled to capacity by 5a. That left most of the participants scrambling to find additional parking along the roadway. I had driven in the night before to spend the night, so was ideally situated for the morning start. I got started just before 6a and sunrise with the larger share of the group, some having started earlier, others still looking for a parking spot. The hike starts off with a gentle decline as it makes its way down to the San Joaquin River at the trail junction for Shadow Lake. After crossing the river on a nice bridge, the Shadow Lake Trail begins climbing in short, steep switchbacks to Shadow Lake. I reached the lake with a few others, took the requisite photos including one of Volcanic Ridge East, then continued on the trail around the east side of the lake. Half a mile past the lake we reached the second trail junction with JMT, and folks began to hesitate, knowing we needed to leave the trail somewhere around here. Five of us were soon heading cross-country, looking for a way across Shadow Creek. There was no clear way to get across with our boots on, so we ended up taking them off and wading across at a shallow bend.

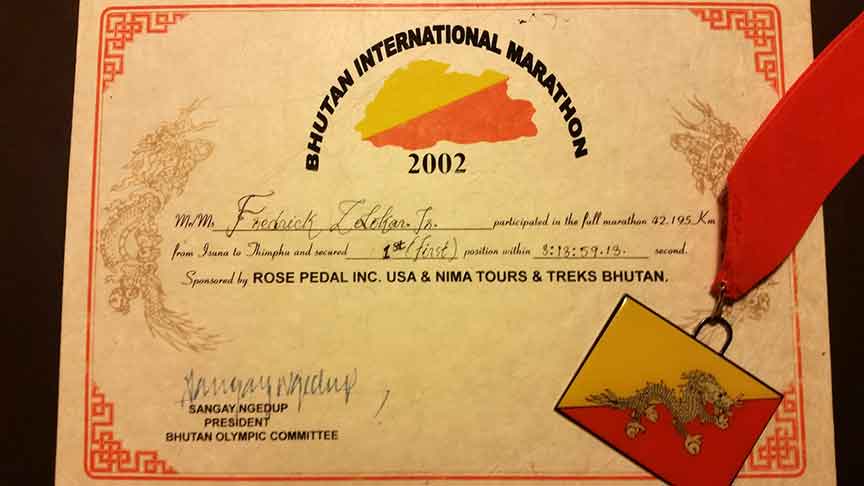

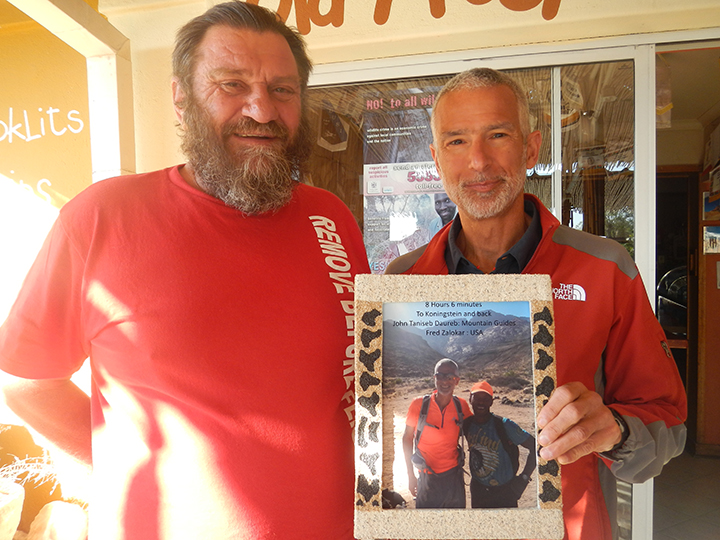

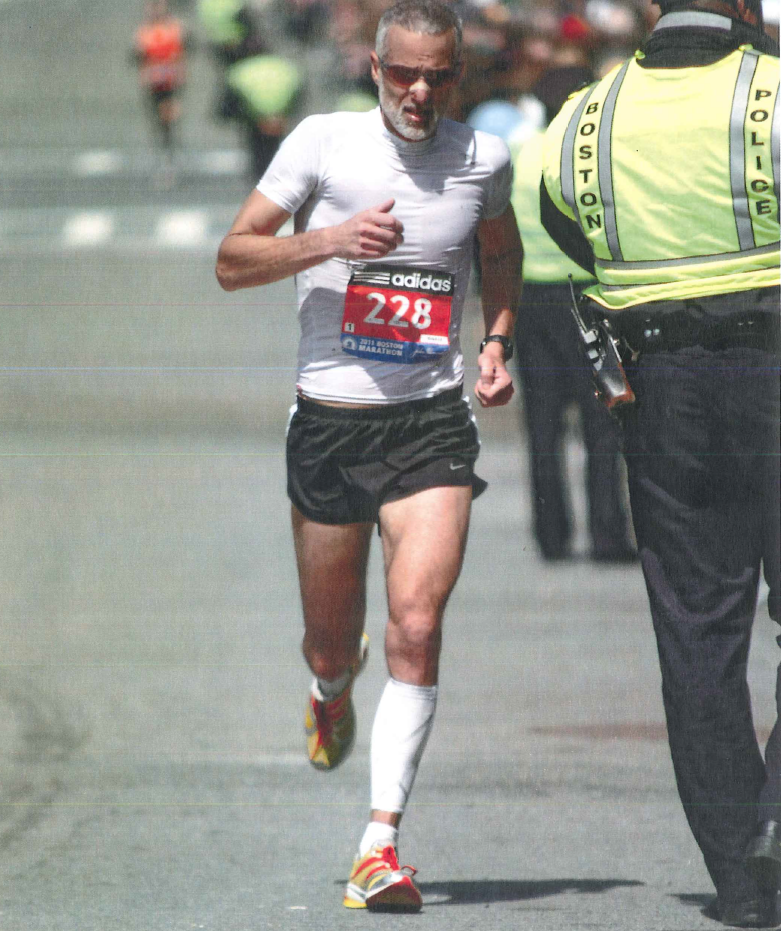

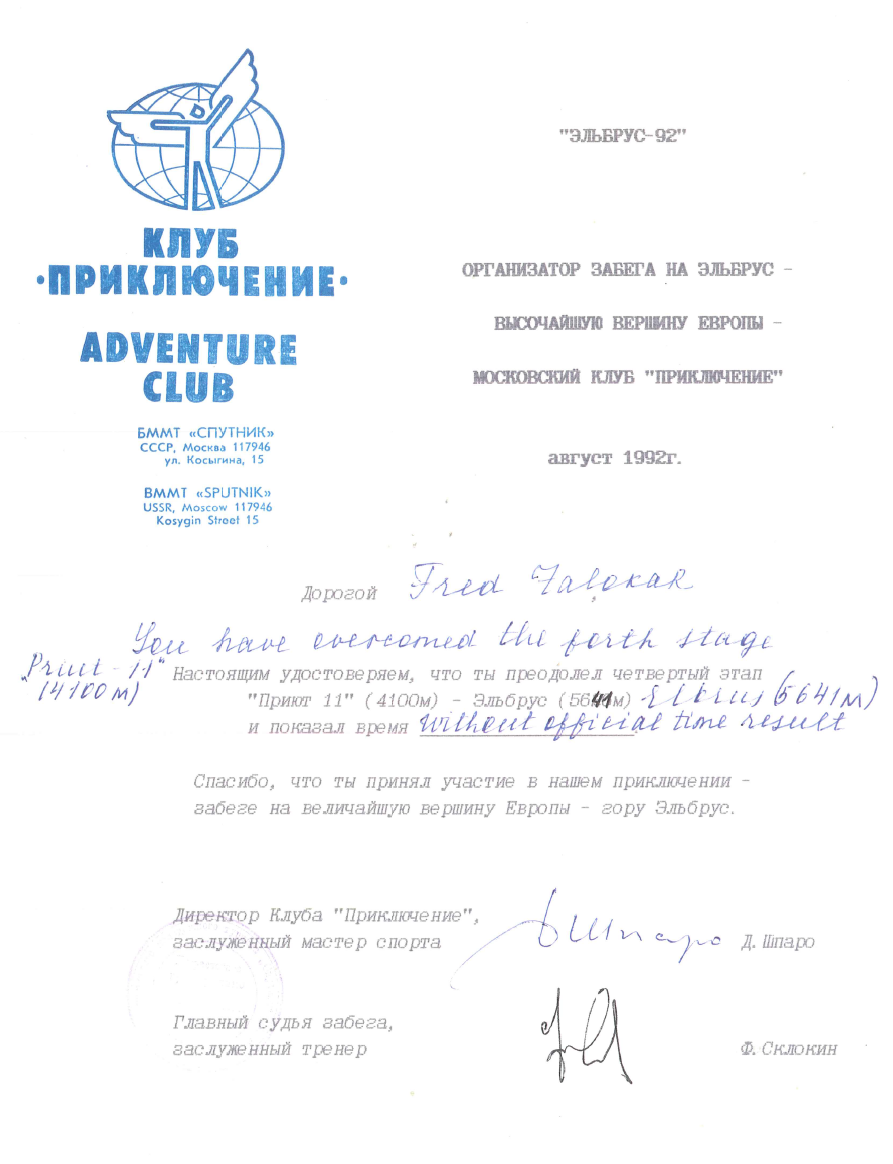

Once on the other side, the going gets steep quickly as we headed up slopes leading pretty directly towards the summit. I was out in front keeping a strong pace, while the other, initially doing a good job of following, dropped back one by one until I was on my own. Once above the forest, I had a clear view of the summit to the south, eyeing what looked like a neat chute going directly up to a notch just west of the highpoint. The chute was partly filled with snow and probably too hard to get up without axe or crampons, so I aimed to the right for what would pass as the NW Ridge. There was some nice class 3 scrambling along this, though most of it was class 2. I spied a pair of climbers ahead of me that turned out to be the Shaper brothers. I caught up with Andrew before reaching the notch, but David kept a strong pace and would beat me to the summit. The summit looks tough from a distance. Cliffs surround it on three sides, but by fortunate happenstance, there is a class 3 chute on the southwest side just past the notch that could get us to the summit without too much trouble. David Quatro was already at the summit with the other David, and it appears Fred Zalokar, a new participant, had already been to the summit and left. We eventually collected nine at the top over the next 20min as we rested up and enjoyed the fine views across the Ritter Range in a panoramic view stretching south to west.

The obvious bonus peak was Volcanic Ridge West about a mile in that direction, but having already visited it I was more interested in unnamed Peak 10,213ft, a little further to the southwest. It seemed no one else shared my interest, so I packed up to start back down by myself. I met Mason just below the summit, pausing as he told a humorous tale of others who had tried to follow him across a difficult route from the west. They would eventually find their way around the difficulty, but I would be gone by then. I descended a wide gully on the south side of the ridgeline, just below the notch we had crossed earlier. It was loose talus and sand, and though it did not have a quick boot-ski descent line, it went quickly enough to get me down in about 20min. The gradient eased as I began a lovely cross-country trek down this isolated drainage that would eventually connect with the Minaret Creek Trail. I kept to the right (west) side of the drainage in order to skirt the base of a subsidiary ridge of Volcanic Ridge West, traversing into the next minor drainage west where I could then climb up to Peak 10,213ft. I was happy to find that this worked quite nicely, better than I had expected. Once I’d crossed the shallow drainage, the ascent up the NE Ridge proved enjoyable class 2-3 scrambling to a rocky summit with a stunning view of the Minarets to the southwest. It took only an hour and twenty minutes to get between the two summits, and as it was only 11:10a, I had much of the day still ahead.

My plan had been to descend to the Minaret Trail and follow that down to the JMT which could then be followed back to Shadow lake. With so much of the day remaining, I decided on the more scenic return around the west side of Volcanic Ridge, a route I hadn’t used in more than a decade. I descended off the north side of Peak 10,213ft into a green meadow where a large party of about 10 were camped above Minaret Lake. Six of them were relaxing in camp chairs arranged in a straight line as though watching a sporting event at the polo grounds. They asked me how the climb was, but didn’t seem much inclined to leave their comfortable positions even after my glowing review. I continued west down to Minaret Lake where I picked up the trail leading up towards Cecile Lake. I had forgotten that the trail ends before reaching the lake and doesn’t start again until beginning the descent to Iceberg Lake, leaving a 30min stretch of boulders and talus to negotiate. With the stunning surroundings, I didn’t mind this as much as I might have in a different location. As I was going by Cecile Lake I noted that it appeared I had it entirely to myself, and decided on a whim to stop for swim. The water was quite refreshing, though I didn’t stay in it for more than a minute. The use trail that’s developed between Cecile and Iceberg Lakes is pretty crappy to start but gets better, becoming a regular trail before it passes by the outlet of the lower lake. I stopped here for a second swim, my small effort to compete in the Aqua Jersey. On my way down to Ediza Lake, I stopped just past its outlet when I spotted a couple of familiar faces. My brother Jim, looking like John Muir these days with a huge, bushy white beard, was joined by Evan Rasmussen and his brother. They had been fishing the lake for maybe an hour with no success, but they’d done better earlier in Shadow Creek and didn’t seem to mind the current lack of action. After about 10min I gathered myself up and continued down the trail.

It would take me another two hours and change to find my way back to the parking lot at Agnew Meadows, finishing up by 3:30p. I saw plenty of folks on the trail between Ediza Lake and the TH, but oddly no other Challenge participants. Most of them had gotten back before me and I found a few in the parking lot, including Tom and Iris who’d made it back 15min earlier. After returning to Mammoth Lakes, I got a few supplies in town before heading off to McGee Creek where I would spend the night with a handful of other participants, likewise sleeping in their vehicles.

Fred had gotten back in 4h25m, hours before anyone else. Granted, he had only gone to the Challenge peak and returned, but it was still less than half the time I spent on the trail. With similar performances over the next few days, Fred would establish an insurmountable lead right from the start, the only question being, would he be able to finish the ten days? In a similarly commanding fashion, Grant would visit seven summits on the first day to establish a lead in the King of the Mountain Jersey that he would never relinquish. His summits included Clyde and Eichorn Minarets, no easy bonus peaks by any measure. He was the last to return to the TH, having spent almost 14hrs on the go.

Scheelore Peak — Peak 11,899ft

Mt. Baldwin — Peak 12,388ft

Sat, Aug 8, 2020

Day 2 of the Sierra Challenge

Day 2 of the Sierra Challenge had us visiting unofficially named Scheelore Peak in the Mammoth Lakes area, less than a mile south of Mt. Baldwin. Our starting point at McGree Creek has been used by the Sierra Challenge a number of times over the years, most recently in 2018 for McGee Pass Peak. Our route would take us up past the Scheelore Mine on a section of trail I’d never traveled on the east side of the Baldwin Crest. In addition to the Challenge Peak, there were two unnamed summits that I was interested in, rounding out the last of the peaks around Baldwin that I’d yet to visit.

A group of around 10 started off from the parking lot by 6a, just before sunrise. We soon entered the John Muir Wilderness, making our way up the trail with the familiar array of peak on the right side of the canyon – McGee, Aggie, White Fang, Baldwin. The rocks take on colorful hues from chalk white and grays to orange and brown. On paper it would seem a shorter route might be found going cross-country upslope where the trail turns to the south. Grant and Clement paused to consider just this. Grant would end up taking a route directly up to Mt. Aggie, then onto White Fang and Baldwin. Clement chose to stay with the pack on the planned route. Further upstream, logs had been laid across the creek to make the crossing fairly tame. We passed by a few folks still asleep in their tent as we continued further through forest. At the first trail junction we turned right to begin the gradual climb up to Scheelore Mine. The trail doesn’t get a lot of use and is hard to find in a few places, but for the most part it was in decent shape. At one time it was a road used to get supplies up to the mine, which is still evident in many places. After meandering to get through the forested areas, the trail/road breaks out into more open terrain where Scheelore Peak first comes into view. Cliff bands and steep slopes suggest it will not be a trivial ascent.

While most of our party collected at the unnamed lake below the mine to fetch water and take a short break, I turned off the road to start making my way up the SW Slopes of Peak 11,899ft. It was a somewhat tedious ascent up talus and broken rock, taking about 25min to reach the top. I would periodically look back to see if anyone was behind, but it seemed no one shared my enthusiasm for this not-so-great summit. It did offer nice views, not only of McGee Canyon to the northeast, but also the other two summits, Peak 12,388ft to the southwest and Scheelore Peak immediately west across the drainage. It was not clear just how we might be able to reach Scheelore Peak with cliffs dominating the upper half of the mountain. A red band of rock starting above the talus slope and ascending diagonally to the left seemed to offer one possibility. I noted the string of participants north of the lake heading in that direction as I started off Peak 11,899ft. I made a descending traverse towards the mine to save some elevation loss. I could see the others make a cursory examination of the mine ruins before starting up the talus slope towards the red band, and they were all well ahead by the time I reached the road and the mineworks at its end.

Once I’d ascended the talus slope, I started to scramble the class 3 slabs on my left to shortcut the route taken by the others who first went to the saddle above before turning left. Mine wasn’t the best choice, as I found a small handful of rocks coming down the face, alarming fast since there was little to slow them down. One of these was baseball-sized and I started to think that perhaps not all above me were being careful. I reached the red band about the same time that three climbers were coming down. One of these was Fred who, having already been to the summit, was in great spirits and making quick work of the outing. The other two were the Shaper brothers who were spooked by the rocks coming down from above and decided to leave what seemed to them a bowling alley. After the three of them passed me, I saw no more rocks come down. A few folks were high on the red band near the crest where it was steepest, going slowly. The better route had been pointed out by Fred on his way down, a ramp ascending to the right that would land on the crest closer to Mt. Baldwin. This class 2-3 route proved safer than the class 4 route along the red band.

I reached the crest soon after 10a where I met up with a few others. It seemed most folks were heading to Baldwin first, so I turned right to follow them. We were all fooled by a false summit into thinking it was nearer than it was, but once the deception was realized, momentum had us continuing to Baldwin regardless, and of course those that hadn’t been to Baldwin were probably more interested in this SPS summit anyway. I found half a dozen of my compatriots at the summit when I arrived at 10:25a. I had been here with a different half dozen participants ten years earlier when we were doing White Fang. I found the old entry in the register that was still in good condition. Grant came up from the north side from White Fang while we were milling about. He reported passing Robert and Kristine and said we should expect them shortly, but I could see nothing of them along the visible stretch of ridgeline. Before starting back down, I reminded the group of our need to be cognizant of rockfall when others are below. I would repeat my mini-lecture to others as I came across them.

The ridgeline between Baldwin in Scheelore is class 2. The hardest part was the initial stretch, becoming a pleasant walk for most of the way. At the saddle, we passed by a rectanglar arrangement of rocks that we had trouble guessing their purpose – perhaps the foundation of an old cabin that once stood here? Mason and Gong came wandering back from the summit soon after that, taking their time and in no particular hurry. After reporting finding no register, I let them sign the one I’d brought for this purpose. I got to the top with Sean C and Grant where we left the register, then talked each other into continuing south along the ridgleline to the next summit, Peak 12,388ft. It would take a little over an hour to cover the mile of ridgeline, the best scrambling by far on the day. Grant of course was much faster, but he hung around long enough to help with some of the tricky route-finding before blasting away. This was the hardest climbing I’d done with Sean and he was showing himself to be a strong scrambler. There were knife-edges to negotiate – he even pulled out his camera while balanced atop one of these – and spooky downclimbing on loose rock. We kept an eye on our left for possible descent routes to avoid having to come back across the ridge on the return. Grant was waiting for us at the summit, seeming to be in no real hurry to get on with the rest of his day. When I asked where he was heading next, he pointed to the southwest towards McGee Pass Peak with a steep 500-foot drop inbetween. To my eye, the ascent across the gap looked awful but Grant sort of shrugged it off with a smile. To his eye, it probably seemed a minor obstacle. He planned to ultimately reach Red Slate Mtn before heading back. He soon got up and said his goodbyes, disappearing quickly down a chute just to our south.

Barbara and Gordon had left a register here in 1985, with half a dozen other entries since then – two of these were Scott Barnes and Sean O’Rourke on a previous Sierra Challenge. When we’d had our rest, Sean and I returned a short distance back along the crest before dropping off the east side to take advantage of a class 2 route we’d spied earlier. It was easier than the ridge traverse but tedious, getting us down to easier ground in about half an hour. Once down the talus slopes, Sean and I chose routes through slabs found below. My more direct route got me to the nice little meadow sooner, and after seeing that Sean was mostly down his route, I continued back on my own. I reconnected with the old road and followed this down, taking shortcuts with the help of the GPSr. Just as I reconnected with the road again after one of these, I heard Mason’s voice behind me on the trail, Zee and Gong in tow. We hiked together only a short distance before they slowed their pace and let me continue on my own. It would take another hour and a half to make my way back down McGee Canyon to return to the trailhead by 3p.

Since I was planning to sleep in my jeep again this evening, I had nowhere in particular to be and no reason to head off, so I stuck around for the next several hours until most of the participants had returned. Beer, snacks, and a bit of relaxing did wonders for a tired body. Later, a handful of us would drive up Rock Creek Rd to spend the night at the TH outside the packstation. There was surprisingly little traffic after sunset and I slept quite soundly there…

Fred finished more than three hours ahead of everyone else, ensuring his lock on the Yellow and Green Jerseys. Meanwhile, Grant was distancing himself in the Polka Dot jersey. He didn’t make it to Red Slate Mtn, instead choosing a longer, harder route to Red and White Mtn several miles to the south which would allow him to tag other bonus summits. He now had 15 peaks in only two days. Emma and Zee were tied for the White Jersey with identical cumulative times.

Larkins Peak — Peak 11,940ft

Sun, Aug 9, 2020

Day 3 of the Sierra Challenge

Unofficially named Larkins Peak is located in the Mono Recesses area north of Mono Creek and well off the Sierra Crest. The name derives from the two subsidiary creeks on either side of it – Laurel Creek on the west and Hopkins Creek to the east. The summit has more than 600ft of prominence which had garnered my attention and its subsequent inclusion on this year’s Challenge. The quickest way to reach it is from the east, going over Half Moon Pass from the Rock Creek drainage. It would be the hardest of the first five days of the Challenge, with 6,500ft of gain spread over 16mi. Our starting point was the pack station along Rock Creek Rd where a number of us had spent the night sleeping in our vehicles.

The trick with the Half Moon Pass route into the Mono Recesses is finding the start of the use trail. Despite having used it already on several occasions, I led our line of eager participants into the pack station and immediately got lost – “Uh, this doen’t look right…” was all I could muster before one of the pack station folks working on some equipment pointed us in the right direction. Once on the pack trail heading south on the outside edge of the property, I knew to look for a trail forking west. I was about to give up and suggest we must have passed it when someone saved me with, “Is this it?” It was, and we were off and running. Not exactly running, but fast-pacing it along the trail as it makes its way through forest in the direction of Half Moon Pass and the Sierra Crest. There is more than one thread to the trail and each can be lost easily if not paying close attention. As a result, the group fragmented quickly, scattering folks about the cirque on the east side of the pass. Once in the upper half of the bowl, the trees thin out and one gets a view of the crest, though the pass is not exactly obvious. I pointed out what I believed to be the correct notch to the few companions I had with me, actually getting it right, a little to my surprise. Not everyone would get it right, but enough did that Sean R and I found a handful of other folks at the pass when we arrived at the end of the first hour. Fred had already gone over the other side, but David, Emma and a few others were pausing to catch their breath here.

Sean and I almost immediately went over the other side and down the loose, sandy chute to avoid congestion and the dangers of rockfall if too many try to go down at once. Ahead of me, Sean ended up taking a more southwesterly line down to Golden Lake while I turned northwest to head more directly to the north side of the lake where I expected to pick up a use trail. This left me on my own, and in usual fashion I didn’t wait around for anyone to catch up. Below the lake’s outlet, I found the use trail and followed it down to the Mono Creek Trail. Once at the junction, the trail becomes a well-worn path which I continued descending. Larkins Peak can be seen rising high above the drainage shortly before reaching the trail junction with the Hopkins Lake Trail. Once at the junction, I was some 600ft lower than our starting elevation, marking the start of the 2,800-foot climb up to the peak. The spur trail was in good condition and easy enough to follow all the way to the lake, found about a mile northeast of the summit. Where the trail peters out near the edge of the lake, I went west around the lake’s southern end and continued cross-country, now mostly above treeline. My route led over the North Ridge of Pt. 12,056ft, then into the cirque on the north side of Larkins Peak. I had still not seen another soul since Sean back at Golden Lake hours earlier.

The only really tedious part of the route so far was the ascent ahead of me, climbing the steep, loose headwall at the south end of the cirque that would take me up to the saddle between Pt. 12,056ft and Larkins. As I started up this, I noticed a climber coming across the cirque behind me, Clement as I would soon find out. Almost casually, he caught up to me with seeming ease, we waved, spoke briefly, and handily beat me up to the saddle. The going from the saddle to the summit gave no respite, not as steep perhaps, but the broken rocks became larger, requiring more effort to surmount them. Seemingly out of nowhere, Fred came clambering down from above. It should have been no surprise, but I thought maybe today my route-finding would get me to the summit before him. No such luck. We talked about his idea of bypassing Hopkins Lake on the return by dropping down the southeast side of the saddle directly to Mono Creek. It seemed a good idea, but because I wanted to visit a bonus peak to the north, I wouldn’t follow suit. Later, Fred would report that the alternate route worked quite well.

It was almost 10:15a before I had joined Clement at the summit. Well, I wasn’t first or second, but at least I was third, right? We would leave a register here denoting that, but I would be wrong. Chris Kerth had beaten even Fred to the summit, I came to find later. I enjoyed the views which took in most of the Mono Recesses. I was intrigued that Lake Thomas Edison could just be seen below Mono Creek to the west. Ritter/Banner and a number of Yosemite peaks could be seen to the northwest, Red & White, Baldwin and the previous day’s peaks to the north. We hung around the summit for about 15min or so, but it seemed no one else was near so we headed off towards the nearest bonus, Peak 11,940ft. We started along the ridgeline connecting the two summits, but it was soon clear that this would be tedious with large granite blocks piled haphazardly along the initial portions of it. As we dropped off the crest we noticed a group of four heading up in our general direction. We paused to meet briefly with Mark, Sean, Chris and David, then continued traversing the east side of the ridgeline for another half hour to reach the saddle just south of the summit. With Clement well out in front, I was making my way up from the saddle when I spotted someone on the way down. It turned out to be Chris Kerth. I had guessed that he’d gone to the bonus peak first and was now on his way to Larkins, but quickly found that he’d already been there. This Chris was sneaky and fast. I asked if he’d found a register on top, and after replying that he had not, I let him sign one of the registers I was carrying with me before we parted ways.

Short digression. In my travels around the west side of the Sierra this summer, I came to notice that Chris Kerth had been to many of the obscure summits I was visiting. Based in Roseville near Sacramento, he’d spent quite a bit of time collecting all sorts of summits in the Northern Sierra and elsewhere in the state, over 1,000 in all, many of which I’ve yet to set foot on. On LoJ, he had somehow snuck up into 7th place on the list of CA summits without me taking notice, ahead of the likes of Richard Carey, Mark Adrian and a host of others. In looking at his recent ascents, I saw that he’d been to Balloon Dome and Pincushion Peak, among other obscure summits in the Ansel Adams Wilderness that I thought were impressive to do together on a backpack trip. So I contacted him through PB to invite him to the Sierra Challenge and was happy that he accepted, even if just for only one day. Turns out he’s pretty darn fast, too. I hope we’ll see more of him in the future.

I reached the summit of Peak 11,940ft by 11:15a, finding Clement relaxing in his usual fashion. He had surveyed the northwest side of the peak already, suggesting cliffs would recommend against a descent on that side. So after leaving our new register, we headed back down to the saddle, then dropped off the southeast side. At the base of the class 2 talus slope, we parted ways as I headed down towards Lower Hopkins Lake and Clement headed northeast towards Robber Baron Peak. He would be the last participant I would see for the rest of the day. I returned to the lake to pick up the trail, but was soon distracted when I came across a nice little swimming hole along Hopkins Creek. I stripped to take a short but refreshing dip before continuing on my way. I decided to skip the trail so I could enjoy some cross-country adventuring on my way down to the Mono Creek Trail. Once back at Mono Creek and the main trail, I settled in for the several hour hike back up to Half Moon Pass. I discovered the older, now abandoned version of the trail between the Pioneer Basin junction and the Mono Pass junction. This worked nicely to keep me from running across other users including at least one packtrain bringing provisions down from Mono Pass.

When I was back at Golden Lake I stopped for a second swim, finding the waters too idyllic-looking to pass up. I was back up to the pass by 2:30p and soon cruising more easily down the east side. It would take another 50min to find the trail and my way back to the pack station, finishing up by 3:20p. I was the second one to return, Fred having finished up several hours earlier and already on his way. I would run into him later at the Vons in Bishop where we both were staying the next few nights at the Motel 6. This would be my first night sleeping in a bed in almost a month, and I must say, I’d almost forgotten how luxurious that felt…

Fred continued to increase his lead in the Yellow and Green Jerseys. Grant maintained his lead in the Polka Dot with 20 peaks in three days, five ahead of Clement. Zee took a rest day, leaving Emma in the lead for the White Jersey.

Peak of the Four Winds — Peak 12,580ft

Mon, Aug 10, 2020

Day 4 of the Sierra Challenge

Day 4 of the Sierra Challenge saw us visiting Peak of the Four Winds on the Sierra Crest northwest of Four Gables. The name is given in Andy Smatko’s Mountaineer’s Guide to the High Sierra, a book that went out of print almost as soon as it was released in 1972. Our starting point was the Pine Creek TH. I’d been warned that a large portion of the parking lot had been roped off by the pack station folks, but when we convened there in the morning there was plenty of room for our vehicles and only a few spaces roped off. I was the last in line this morning at the 6a start, having trouble getting my GPSr working right from the start. Though only a few minutes behind the large group, it would take some time to catch up as we followed the old mining road up towards Pine Lake. I would eventually catch up to most of them singly and in pairs over the course of the hour and half it took to reach the first lake. Beyond this the going gets easier for a while as the trail passes by lakes and through forest on the way up towards Pine Creek Pass. I caught up with Chris at the Honeymoon Lake junction and together we made our way up the trail for another 30min until we were just below the pass. Chris stopped to get water while I continued up to the pass.

I waited a few minutes at the pass when I arrived around 8:40a, but Chris didn’t look to be coming up. I turned off the trail to follow the ridgeline east. This was a pleasant walk with an easy gradient and all class 1-2. Chris hadn’t bothered to hike to the pass, taking a shortcut that got him ahead of me. Once I’d caught up for the second time, we continued together, aiming first for the bonus Peak 12,580ft. This was pretty straightforward all the way to the easy summit, or so it seemed. We found Clement there ahead of us, thumbing through a register left by MacLeod/Lilley in 1985. It was a pretty busy register with more than 30 pages of entries. Well out in front, we wondered why he hadn’t already left for the Challenge peak to the south. He pointed to another point about 400ft to the northwest, asking “Is that point higher?” I looked carefully, lining up its summit with the one we stook upon and noting the further point’s line far to the northwest against Bear Creek Spire. It certainly seemed higher, and I recommended that to be fair we should probably visit it. With Zee joining us as a party of four, we set off along a very rugged section of ridgeline that none of us had any confidence would actually work. Clement did a fine job out front finding a class 4 route that would work, though not without some hesitation and some dicey sections. It took us about 20min to cover the short distance, but it was the best scrambling we’d found so far on the Challenge. I took an elevation reading from the GPSr and compared it to the one I’d taken on the first summit, and it came out about 10ft higher. Elated with our success, we left a register here before carefully reversing the route.

I went back to the lower summit to leave a note for other participants who would probably visit later, then continued on to Four Winds. It would take 40min to traverse between the two summits, most of it class 1-2. Somewhere in the middle was a class 2-3 section of ridge to get over and it was here that I ran across Genevieve on her way to Four Winds. About half a dozen had already reached the summit when the two of us arrived about 11:20a. The peak offers a spectacular view of French Lake, Humphreys Basin, French Canyon and a host of familiar peaks to the west. Mt. Tom rises dramatically to the east while Mt. Humphreys does likewise to the south. There was a register placed in 2008 by Mark Riner that had the peak as “Ramu Point,” with a handful of other entries before our arrival. While taking a break at the summit, I got to thinking that it might be shorter and faster to return via the Gables Lake Trail rather than return to Pine Creek Pass. It wasn’t obvious that one could get down the east side of the crest due to cliffs, but it seemed worth a try. The others were either not interested or planning to visit the bonus peak three of us had climbed earlier, leaving me to do this on my own.

We packed up as a group and started down, the rest of the group descending the North Slopes while I turned right to investigate a saddle to the northeast. As I expected, I couldn’t see the entire way off the east side but the saddle offered a good starting point. I might get down 300-400ft and find myself cliffed out, but I had plenty of time and energy to reclimb and return via Pine Creek Pass if necessary. The route worked quite nicely at class 2-3, taking about 30min before I reached easier ground. There was one tricky spot that had me hanging by some scraggily pine branches (probably avoidable), but overall it was quite reasonable. Once down to a small tarn in the upper part of the basin, the next 40min were spent making my way a little over a mile down an easy gradient, following the creek to Gable Lakes. I was careful to avoid anything that looked like a moraine, staying close to the creek for the most part. Interestingly, the creek disappears quite suddenly under some bushes in a shallow depression, going underground. Surprisingly, the topo map has this exactly right, showing the creek ending in a small lake with no outlet. The lake can only be present when the inflow is greater than the outflow capacity, so with little snow remaining, the lake has drained out. After climbing out of the depression and continuing east, I eventually returned to the creek and soon reached the higher of the Gable Lakes, making my way around the north side. After crossing the outlet, I climbed a short distance up the opposite side and found the trail I was looking for almost exactly where it was depicted on my GPSr.

It was now 1p and I had simply to follow the trail back down to the trailhead about an hour and a half away. The trail goes by some dilapidated cabins with mining gear and personal effects scattered about. Much of the tram that once carried ore more than 4,000ft down from the side of Mt. Tom still stands, its thick wooden beams and solid engineering looking set to last another 100yrs or so. The trail stays high on the west side of Gable Creek as it descends, swinging around to the west before switchbacking down to the Pine Creek trailhead. I arrived there at 2:25p, just five minutes before Asaka and baby Leif returned from their hike to Pine Lake. We set up camp here for the next few hours to wait for the others to return. An elderly woman came out from the pack station while I was sitting there and began to lament about 5-6 cars that were parked where they weren’t supposed to be – “How am I supposed to turn my trailers around?” Knowing that some of them were from our group, I got up to speak with her and try to settle her down. I told her that most of them were just day hikers who would be gone in a few hours, and apologized for the inconvenience. She continued, “I put ropes up and No Parking signs, why would they park there?” I admitted I didn’t know, but I looked around and noticed there were in fact, no such signs. “Where are the signs?” I asked. She paused for a moment before replying, “I took them down.” I sort of chuckled before asking, “Well, how would they know they weren’t supposed to park there?” Her face changed suddenly from a scowl to a sly grin before responding, “I guess I should lighten up.” We became fast friends after that, and I again reassured her most would be gone before evening. She got back in her truck and went about whatever business she’d originally planned back in town. The other participants came trickling in over the course of the next few hours. We had beers and snacks and stories to share all the while.

My descent route proved a good one, getting me back more than an hour before everyone else with the exception of Fred – he descended the same way and was back more than hour before me. His lead in the Yellow and Green Jerseys was now more than 11hrs. Grant added another six summits to his total, giving him 26 peaks in four days and increasing his lead in the Polka Dot Jersey. Emma maintained her hold on the White Jersey.

Peaklet

Tue, Aug 11, 2020

Day 5 of the Sierra Challenge

Day 5 of the Sierra Challenge was one of the easier ones planned, about 7mi roundtrip with 3,500ft of gain. It was designed to make for a half day’s effort, leaving us the afternoon for the annual cook-off at the Church of Grundy. COVID interferred with the cook-off plans, but we left Peaklet on the agenda. It turned out to be a decent summit with some dramatic scrambling.

The crux of the day was the drive to reach the TH, really only suitable for 4WD with high-clearance that could make it to the end of Buttermilk Rd. I drove up the TH the night before and was one of only two vehicles to make it – Sean Reedy’s Suburu Ascent being the other one. Most of the cars were congregated about 3mi down the road, necessitating extra hiking to make up the difference. Iris, Tom and Emma were the only ones to reach the TH by around 6:15a, so with Sean and I making a party of five, we set off on one of the spur roads that soon ends at the Wilderness boundary.

We had originally planned to hike around the peak to Longley Reservoir and then up the backside of the peak which is reported by Secor to be class 3. During our short hike along the trail, we reasoned that we could make a much more direct ascent up the peak’s East Face. The route looked to have plenty of vegetation that we expected would make for decent footing, and with that expectation we set off cross-country. In practice the route turned out to be tediously sandy and seemed to only get worse the higher we got on the mountain. With 2,600ft of gain from where we left the trail, it would take close to 2hrs to complete the climb. At least the views were pretty nice – Mt. Locke and Checkered Demon were colorfully displayed to the south. Mt. Humphrey’s and its East Ridge dominated the scene to the west. The tamer environs of the Buttermilks dropped off to the east below us.

I was the first of our five to reach the summit, discovering to no great surprise that Clement and Fred had handily beaten us to the top though we had not seen them the whole morning. They had arrived at the TH shortly after our departure and took the roundabout route to the backside, climbing one of two chutes found there to the summit. Or what they thought was the summit. When I joined them on the small perch of the uppermost rocks, I looked across to the north and spied another point of similar height about 50yds off, separated by a 60-foot notch. “Are you sure you’re on the summit?” I enquired. They were not sure. I asked if they found a register (No, they hadn’t) and pointed to a small stack of rocks on the other summit. Reluctantly they agreed that we had to check out the northern point.

Clement led off on the direct route between the two summits. Not liking the look of the climb up to the north summit, I chose to downclimb about 100ft in the chute the others had ascended, then climbed up to the sloping slabs on the north summit’s west side. This proved a bit dicey and I had no desire to downclimb it. Sean and the others had reached the south summit, watching the antics of the three of us. I called up to suggest they *not* use my route. Wisely, the rest followed Clement’s direct route which turned out to be not as hard as it had looked (to me, anyway). By either route, the peak turned out to be more exciting that we had expected and despite tedious ascent route, I was giving the two summits high marks. The GPSr showed the north summit to be about 9ft higher and Jason Lakey had left a crude register here in 2016, writing on a scrap of cardboard and leaving it in a gatorade bottle. He had also left a damaged indian spear point which we found most interesting. We left it in the new register canister we provided for this fine summit.

This was the longest time I’d yet gotten to spend with Fred, our Yellow Jersey leader, who’s usually come and gone from a summit before I’ve reached it. We had seven of us spread out on the not-so-large summit area where the conversation turned to descent routes. Clearly the fastest way would be to go back over the south summit and then bomb down the sand slopes on the east side, but I was curious about the two chutes on the backside of the mountain. It was just 9a, so I figured I had plenty of time to do some exploring and decided to head down the northern of the two chutes (Fred and Clement had ascended the southern one). The descent from the summit was some stiff class 3, but nothing as dicey as the route I’d used to ascend the north summit. The chute was mostly class 2 with a few constrictions that called for some more class 3 scrambling. The bottom of the chute dropped out over what seemed like a cliff, but it was easy enough to traverse southwest across easier ground before reaching the talus slopes at the bottom. From below, the northern chute is difficult to discern and only the southern one is obvious. As Clement and Fred reported, the southern chute is fairly easy and straightforward, leading to the notch between the two summits. The only real plus for the northern chute is a slightly easier scramble to the higher north summit once the chute has been ascended.

I made my way north across sandy benches and granite slabs to the east of Longley Reservoir. The water is a sickly green, the result of glacial silt and probably devoid of fish. I had entertained the idea of swimming in the lake, but the silt somehow discouraged me. Emma, meanwhile, had decided to take my descent route about ten minutes after I had headed down. I never did see her, but she stopped for a swim before returning to the TH about 20min after me. The others all decided on the east side descent. Mason and JD had gotten a later start, and were ascending the south chute on the backside while I was descending the other chute – I never did see them until after I’d returned. I eventually found the trail below the lower lake on the north side of the creek and followed the sandy path for much of the last hour back to the TH. Sean had arrived about 20min before me and was there at the TH. Fred and Clement had gotten back more than an hour before Sean and had probably already done the three miles back to their vehicles.

I waited around for most of the others to return including Emma, Iris, Tom and JD. We then drove down to the other vehicles and used my towstrap to pull Emma’s truck out of the deep sand she’d gotten stuck in. So much fun for one day and it wasn’t even noon yet…

Hermit South

The Socialite

Wed, Aug 12, 2020

Day 6 of the Sierra Challenge

Day 6 would be the hardest of this year’s Sierra Challenge, a 21mi effort with more than 8,400ft of gain. Unnamed Peak 12,342ft lies deep in the heart of Kings Canyon NP, a short distance and slightly higher than its more well-known neighbor, The Hermit. In an email exchange with Eric Su six months earlier, he informed me that the summit was called “The Socialite” in the register which he had visited in 2018. I thought it was a nice complement to The Hermit and used that as the name during the Challenge. Only later would we realize that Eric had climbed an adjacent summit, leading to some naming confusion. After the fact, to avoid having two summits with the same name, I called the Challenge peak Hermit South and use that name in this report. Our route to reach it would start at North Lake, go over Lamarck Col into Darwin Canyon, descending to Evolution Lake before traversing south across the upper basin of Evolution Valley, and finally climbing to the summit. Most of the folks heading over Lamarck Col were heading to other destinations, notably The Hermit and Mt. Darwin. Our 5a start would allow for a full day and then some. Not everyone would get back before dark, with some not returning until nearly midnight.

Our route began at the North Lake parking lot by headlamp, heading up the road through the campground and then onto the Lamarck Lakes Trail. We were able to put our headlamps away after about 30min when in the vicinity of the Grass Lake Trail junction. Our group was spread out by this time and only a handful were still in sight when I reached Lower Lamarck Lake and crossed its outlet on a rickety set of logs. The trail continues up towards Upper Lamarck Lake with a helpful sign now installed where to turn off for Lamarck Col after crossing the creek a second time, but before reaching the upper lake. I caught up with Zee and his two pals at the top of a series of short switchbacks that lead to the next drainage southeast of Upper Lamarck Lake. We hikedthe sandy bowls in the parts of the mountain above treeline to r each the small lake below Lamarck Col. The snowfield was still present requiring some snow travel, but it had a decent boot track that could be followed without axe or crampons. Just before the pass, a trail-running couple passed by on their way to Mt. Sylla – an even more impressive destination. We spoke only briefly before they went up and over the col and out of sight. I found Sean Casserly at the col, having started early. He asked if anyone else was going to Mt. Darwin. I smiled and told him the three guys just behind were planning to do just that.

I waited less than a minute before going over the pass around 7:25a. It was too cold to wait very long in the early morning chill. I was by myself for the next 30min or so as I descended into Darwin Canyon, following one sandy use trail or another. While following around the north side of the lakes that dot the bottom of the canyon, I came across the trio of Tom G, Tom B and Iris, who had all started before 5a. I settled in with this group for the remaining descent of Darwin Canyon and Darwin Bench below that. By the time we had reachedthe JMT and the outlet of Evolution Lake around 9:15a, we had picked up Mason and Rafee as well. We crossed the large lake’s outlet, passing a couple camped at the edge looking west into Evolution Valley. On the south side of outlet we passed through an older guy’s camp with enough stuff for two or three friends (In fact, he had several friends that were currently off climbing Mt. Darwin.) A large, stainless steel box held a cache of food, obviously brought in by a pack train. I waved to the gentleman as I passed by, to which he asked the group if we were headed to The Hermit. Someone replied in the affirmative and asked if he’d been there himself, to which he responded, “Nine times.” I thought, “Huh, that’s a funny summit to make so many repeat ascents on,” but didn’t give it more attention until someone said, “Hey, that was Doug Mantle!” I made an immediate U-turn. I’ve missed seeing Doug in the wild on several occasions, sometimes by hours judging by the register entries at the summits. I had recently had a lengthy email exchange with him regarding ascent records of Andy Smatko but had never talked with him in person. I went back to introduce myself and take a photo of him in his natural habitat. A few photos were taken of the two of us together, and we were soon on our way. I think the whole exchange took place in under a minute.

In leading our group on the traverse past Doug’s camp, I stayed a bit too high and got us onto some class 3 slabs and steps that slowed everyone down. I had soon gotten ahead, turned around to show Mason a ledge I’d utilized, then lost everyone for good. I crossed the stream at the bottom of the cirque between Hermit South and The Socialite, then started directly up for the NE Ridge of Hermit South. I’d look back occasionally but didn’t see the others and had little reason to, since they were heading to The Hermit first. I stayed on the east side of the ridge to avoid larger blocks on the ridge proper, eventually gaining the ridgeline for the last few hundred yards. It was close to 11a when I topped out, finding Sean Reedy already there. He had started before 5a, too, and was carrying the rope the group planned to use for The Hermit. I thought it was funny that he went to the Challenge peak first, but he surmised (correctly) that he could reach it and get to the Hermit about the same time as the others. While we were chatting there, Grant came up from the east side, having just finished the traverse from The Socialite. A few minutes later, Clement showed up as well, having followed Grant from the previous summit. Sean got Grant to carry the rope since he was faster, and the three of them headed off to The Hermit. I sat around for another ten minutes, in time for Tom B to show up, having taken much the same route as myself. I’d forgotten that he’d already done The Hermit and would be following after me. We hung around for another ten minutes to give him time to take a break. I took some photographs of the surrounding monarchs – Mendel & Darwin to the northeast; Haeckel, Wallace, Spencer to the east; Goddard, McGee to the south, Emerald to the west. We left a new register under a small cairn at the end of our stay.

Together, Tom and I set off for The Socialite, an enjoyable class 2-3 scramble along the connecting ridgeline, much as Grant and Clement had described it. We stayed on the ridge for the descent to the saddle, then stayed on the south side of the ridge on the way up to the second peak to avoid difficulties. It took us an hour to cover the mile distance between the two, arriving around 12:30p. Trey Hawk caught up with us at the summit. He had come out to join the Challenge for a day unannounced, having gone to The Hermit first, soloed it, then continued on to Hermit South and The Socialite. I’d never heard of this youngster, but he was clearly skilled and as fast as Grant & Clement. The register on the summit had been left by MacLeod/Lilley in 1983 and was surprisingly busy with more than 40 pages of entries. A Dylan and Rob dubbed it “Socialite Peak” in 2006 which then became “The Socialite.” Eric’s entry in 2018 confirmed my suspicion that he’d not climbed the Challenge peak after all.

From The Socialite, Tom and I descended the northeast side while Trey followed the ridge to the southeast before turning north. We were headed to Pt. 11,576ft above Evolution Lake that Clement had told us had an interesting register. I lost Tom somewhere on the class 2-3 slopes leaving The Socialite, but met up again with Trey just below Pt. 11,576ft. The interesting register turned out to be an interesting steel box with a tattered and burned and mostly unreadable small piece of paper. Clement’s name was the only one we could discern on the brittle scrap. When I expressed my disappointment to Clement later, he just laughed – I think he was just trying to see if he could get us to do some extra work. Trey and I descended Pt. 11,576ft via different routes, rejoining for a second time at Evolution Lake’s outlet stream. We hiked back together on the JMT and the use trail leading up to Darwin Bench. I stopped to take a swim there while Trey headed off, no doubt at a much faster pace. It was the last I saw or heard of him, but I hope we’ll see more of him in the future.

The swim was a refreshing delight with a fine rock from which to dive into deep, clear water. It was nice to clean off the salt and sweat and give the legs a bit of a rest. After dressing, I downed my doubleshot of espresso to help me with the final climb back over Lamarck Col. It did a remarkable job of getting me up through Darwin Bench and Canyon, though it was wearing off by the time I started the steepest climb an hour later. I took my time getting back up to the col, reaching the day’s highpoint for the second time just before 4:30p. I thought I might start seeing other participants as I descended back down, but I saw no one since Trey and I had parted ways back in Darwin Bench. For a change of pace, I took the old trail down to Grass Lake, bypassing Lower Lamarck Lake and much of the morning’s route. The only person I saw on the trail since Trey was a photographer setting up for a photo of Piute Crags around 6p, not far from the campground. After passing by the TH at the campground and just before I had walked the half mile of road to the parking lot, Clement and Grant came jogging up behind me, all smiles. They had evidently had as much fun today as I had, perhaps more…

It seems that those that had gone to the Hermit first had also gone to Hermit South afterwards, and most of those to The Socialite as well. This meant that some were coming back after 11p, having been out for more than 18hrs. Fred had been to Hermit South and left before I arrived, having gotten back almost three hours ahead of me. His lead in the Yellow and Green Jerseys had gone from Insurmountable to Ridiculous, now more than 11hrs. Grant now had 30 peaks in six days for the Polka Dot Jersey lead. Zee had made it to Mt. Darwin, though his friends did not. He was now within one Challenge peak of Emma who had left for home the previous evening.

Echo Peak

Thu, Aug 13, 2020

Day 7 of the Sierra Challenge

Unofficially named Echo Peak rises above Echo Lake just north of the Sierra Crest and Mt. Powell. The name derives from Andy Smatko’s Mountaineer’s Guide to the High Sierra and is given as class 4 via the NW Ridge. It is imposing when viewed from most vantage points and there were no modern records to be found online. Tom Gundy had taken a picture of it from the northwest recently and suggested one possible line. Kristine Swigart and pals had climbed it two days earlier but gave away no secrets, simply describing it as “Fun!” Our starting point would be Lake Sabrina, complicated by construction efforts taking place at the dam that blocked some of the few parking spots available at the trailhead. Because of the late return many participants had the previous day, there were only a handful for our 6a start – Grant, Clement, Fred, Tom B and Zee (who planned to go to Mt. Wallace instead). I was feeling outgunned by the first three heading to Echo Peak as they were all much faster than myself and it took only a few minutes after we started off that I was hiking the trail on my own.

It had been a number of years since I’d last traveled up the trail as it climbs above Lake Sabrina to Blue Lake. It was nice to revisit this area after a seven years’ absence. I turned right at the trail junction past Blue Lake that would take me to Dingleberry Lake, following it as it descends one drainage and ascends another. I was a little surprised to see Fred just past the creek crossing beyond Dingleberry, two hours after starting out. He was taking it easy today, hiking with Clement and Grant doing likewise a short distance ahead. We followed the Hungry Packer Trail to Sailor Lake, leaving the trail to traverse into the next drainage to the southeast, past Moonlight Lake and then ascending the drainage towards Echo Lake. Grant ended up ahead of the rest of us, and the next time we saw him he was high on Echo’s NW Ridge, though how he got there was unclear. We reached the base of Echo Peak around 9:15a and paused to consider possible routes. We didn’t take to Tom’s suggested route further upslope – it looked kinda hard with snow potentially blocking it (though later it seemed that might have been the easier route). Fred and Clement decided to explore possibilites on the right (west) side of the ridge while I chose to ascend halfway up the drainage before tackling the ridge. Both routes worked, but not easily, in the class 3-4 range. I was found my route a bit dicey and hoped not to have to return the same way. I met up with Clement on the ridgeline about 40min later. Fred hadn’t liked Clement’s chute and went and searching around for an alternate. We wouldn’t see him again for a while. On the ridge we continued higher until stopped by more vertical terrain. We first explored around to the right (south), but found this cliffed out quickly. We might have been able to drop down a steep chute and up another, but I suggested we try around the left side where a ledge gave some hope. This worked nicely, taking me on a traverse across the north side of the ridge and around a lower west pinnacle where I could then start climbing back up. Clement appeared atop the lower west pinnacle via a much harder route. He could see that my route offered promise above where I couldn’t see. More class 3 scrambling got me to the chute on the north side between the west and east summits. From there, it was a fun bit of scrambling along the ridge to reach the highpoint. Clement was right behind me and soon joined me at the summit around 10:30a.

We looked around for Grant but saw no sign of him. We knew he planned to follow the ridge south to Mt. Powell, but this looked like a very difficult prospect. Clement had wanted to do similarly, but after surveying the terrain, decided against it. Later we learned that Grant had indeed gone that way, describing it as a little desperate but doable. I looked around for the register that Kristine had told me she’d left, finding it wedged under a rock near the summit. It was hidden quite well such that Grant never saw it. We signed it and left in the same location. With some discussion, we thought we could make our descent easier by dropping further down the chute we had ascended near the end. As we started down, we spied Fred making his way up. I had to chuckle because this was the first summit I’d beaten Fred to in seven days. He was nothing if not relentless. We continued down as he went up, figuring he’d soon catch up to us. Near the bottom of the chute where it begins to drop away, I found a rap sling on the eastern edge. The descent beyond that seemed a difficult enterprise, so I recommended not doing so. Fred would later report that he had descended this way and it worked well, and Tom G would also report ascending/descending the same. After descending further in the main chute, Clement and I began traversing the ledge system I’d used earlier and returned to the NW Ridge. From there we went all the way northwest to the edge of the shoulder and looked for a way off that side towards Echo Lake. Finding only cliffs, we backtracked and used Clement’s class 3-4 chute partly-filled with snow that made for an interesting descent. After we descended to the easier class 2 talus rubble, we split up, Clement heading west to Picture Peak while I started back down the drainage.

I spent the next 20min or so enjoying the easy descent through the grassy valley, eventually spying a figure in yellow making his way up. I veered over to intercept Tom G and spoke briefly with him. I was surprised (but shouldn’t have been) when Tom told me he’d just spoken with Fred. Seems he’d figured out a much quicker way down from Echo and had gotten ahead without me even suspecting. Tom and Iris had gotten a late start because of the long previous day. Tired and moving slowly, Iris decided to stop at Moonlight Lake and let Tom go ahead. The weather was looking pretty threatening over the Echo Peak by this time, but Tom shrugged it off. He would get lucky with nothing other than a few drops over the next few hours as he made his way up and back. I continued downstream, soon finding Fred taking a break to get some water. He was in fine spirits, describing his fortunate descent route and overall enjoying the day a good deal. He was in a social mood, choosing to hike with me the rest of the day rather than run off ahead. We ran into Iris and Tom Becht by Moonlight Lake. Tom had returned after getting as far as Echo Lake. He had watched the rest of us ascend the various routes on Echo Peak, hung out for a while and then returned back down the drainage, finding Iris at Moonlight Lake. They came over to meet us for and we talked for a few minutes before everyone continued down. Fred and I got well ahead and soon on our own again. It would take us another two hours and change to make our way back down the trail to Lake Sabrina and the TH, finishing up at 2:45p.

I hung around the TH for an hour or so, enjoying an early happy hour with Tom and Iris up their return. Afterwards, I headed back to Bishop where I got a few supplies, found some free wifi to get some pictures uploaded for the Challenge, then headed to Big Pine and the South Fork TH where a number of us would spend the night. Another big day tomorrow…

There were no changes or significant developments in the jersey standings. Grant had had another big day, tagging all three of the Powells, Mt. Thompson and Ski Mountaineers Peak to give him 36 peaks in seven days now.

Middle Palisade

Excitement Peak

Fri, Aug 14, 2020

Day 8 of the Sierra Challenge

Day 8 would be the second hardest of this year’s Sierra Challenge with 6,800ft of gain over the course of 13mi. Unofficially named Excitement Peak lies on the Sierra Crest in the Palisades region between Disappointment Peak and Middle Palisade. It has little prominence, first appearing in Secor’s guidebook as a pinnacle to be bypassed on the Middle Pal to Disappointment traverse. Matthew and I had done just this in 2005 when we did the traverse from Balcony Peak to Disappointment to Middle Pal. Secor gives no actual description of climbing the minor summit and I could find no information online, either. Clearly folks had been to the summit as the locally-derived names suggests it was found to be a spicy undertaking. I didn’t know if I would personally be able to reach the summit, but it seemed a worthwhile adventure and why it landed on the Challenge this year.

We had a modestly-sized group of about 7-8 for the 6a start from the South Fork trailhead. The trail up the South Fork Big Pine Creek is a familiar one, about five miles to Finger Lake if one uses the shortcut to bypass Brainerd Lake. There are two places that seem to change over the years, the first being where to cross the creek. Without a fixed bridge, the crossing can be treacherous in high water, more tame late in the season. Today was closer to the latter and I was able to get across on rickety branches without taking my boots off or, as sometimes happens, falling in. The second change is where exactly to find the Finger Lake shortcut. I was on my own for this section, thankfully, because despite having used it at least half a dozen times, I pretty much botched it this time and ended up on terrain both brushier and rougher than it needed to be. I reached the outlet of Finger Lake by 8:15a, finding Mason just on the other side. Others were not far ahead starting up the boulder fields above the lake. Mason and I followed a route closer to the lake that offered no real advantage over the more direct line further to the west and we got a bit behind the others. Mason was moving slowly today, having not yet recovered from his 19hr+ outing the previous day, and decided to take a rest while I pressed on. He wasn’t feeling it today and would turn back without making it past the glacier – similar to where I turned back on my first effort during the first Sierra Challenge in 2001. I continued up on my own, reaching the edge of the moraine shortly after 9a.

The moraine is the loose pile of rock left by the receding Middle Palisade Glacier. Ahead I could see a couple of figures, Zee and Fred making there way higher still up this loose collection of unpleasantness. I followed their route across a couple of low-angle snowfields to reach the medial moraine between the two halves of the glacier in about half an hour. I would have been better off following the others to the redish rock on the right, marking the standard route up the main chute. Instead, I was curious about the state of Secor’s route, a narrower chute just to the left. I’d brought crampons and ice-axe for just this purpose with the added bonus that I’d have the lower half of this route to myself with less concern for rockfall from others above me. I wandered out onto the glacier at its upper edge and found nothing that looked like the class 2 ramp I recalled when Matthew and I had used it 15yrs earlier. Thinking it was further left than I could remember, I continued along the upper edge of the glacier until I was almost directly under Middle Pal’s summit and found nothing but difficult terrain wherever I looked. I backtracked nearly to where I’d began on the snow before recognizing the ramp above me. Trouble was, the glacier has receded over the past decade and a half, exposing some terribly loose and steep terrain below the start of the ramp. I scrambled up this every so gingerly, but it very unnerving for that first 15-20ft or so, more like class 3-4 than class 2. I quickly found ducks above and the right-leaning ramp that would take me more easily up to Secor’s chute, helping confirm I was on the right route (later I would find I had a similar photo of the ramp from 15yrs earlier that showed it was the same ramp as well as some changes where rocks have shifted and fallen out of position). It doesn’t look like this route sees much traffic anymore, and with the increased danger I could see why. At the end of the ramp I followed more ducks around the corner and into the steep class 3 chute going straight up. The rock quality here is pretty descent and makes for some fun scrambling. The chute merges with the main chute after about 10min where I met up with Zee once more. He was moving more slowly now and I pulled ahead of him as I continued up the main chute for another half hour to reach the summit by 11:20a.

I found Sean K and Sean R already at the summit, Sean R getting ready to start for Excitement. Grant and Clement had already headed off and were out of sight. Sean K had reached his goal for the day and planned to rest up more before starting back down. The 1936 aluminum Sierra Club register was still at Middle Pal’s summit along with a number of booklets covering decades of ascents. I quickly signed into it so as to continue on to Excitement, hoping to take advantage of the others’ route-finding. The distance to Excitement was only about 600ft, but it would take me 45min to traverse between the two. The route starts off as a standard class 3 scramble along the ridgeline, losing little elevation until Excitement comes into view and the ridge drops off steeply. Grant was already at Excitement’s summit and Clement was close behind, following its steep and exposed class 3 NW Ridge, directly on the crest. The route looked reasonable to my eye despite the exposure, until a large block is encountered about 30-40ft below the summit. I watched Clement make an exposed move along a thin ledge at the base of this to reach a body-sized crack, then back off and call up to Grant for some direction. Grant told him he used the crack and then Clement carefully made the same moves, wedging himself in the crack before pulling up onto rocks above. It seemed an awfully dicey proposition to me. Not liking the looks of it, Fred had gone around to the left to look for another way up. Closer to me, Sean R had just finished reaching the chute on the north side of the notch between the two summits, and I didn’t have a chance to see how he got there. I called over to him for some help to which he indicated he’d gone down the northeast side before traversing across. With a few missteps, I finally managed to follow a similar class 3-4 path, meeting up below the notch with Fred already on his way back. He was a bit excited, eager to get off such treacherous terrain and probably wouldn’t be able to relax until he was back at Middle Pal. I was feeling similarly, but internalizing it more and cautiously making my way across. Fred had said that his route was probably easier and encouraged me to use it. After we parted, I moved around to the Northeast Face and was happier with what I saw there – steep, but looking less exposed and with more than one option. As I was moving up this face, Grant and Clement came down to my left, eager to get on with the traverse to Disappointment. They were calmly having a discussion about possible route lines as they disappeared below me. I found the left side of face had easier scrambling, no more than class 3 with good holds and decent rock. When I popped out on the summit just before 12:15p, Sean R was already there, having utilized Grant’s ascent route. Finding no register, we left one of our own to which we added the names of our companions who’d already left. The summit was a wild little perch that could hold a few folks comfortably with a wide-ranging view to the north and south. We exchanged waves with Sean K at Middle Pal’s summit to the west.

Almost as eager as Fred to get off this difficult terrain, we spent only a few minutes before carefully retracing my route off the NE Face. My route on the traverse back towards Middle Pal must have been a variation of the outbound route, because I came across a rap station that I hadn’t seen earlier. The return went quicker, only about 30min to reach Middle Pal’s summit. Zee had reached the summit and was just starting down not far below us. Sean K had left the summit earlier and was somewhere ahead of Zee. I was very careful to avoid knocking anything down with others below me, and for the most part kept to the east side of the chute to minimize having them in the direct line of fire. Near the bottom of the main chute, I came across David Park on his way up. He was probably about 45min from the summit at the pace he was moving, but seemed in good spirits and didn’t seem to mind that he’d be the last one off the summit today. I used the red rock route for the descent, loose and crappy for the lower part, but not really dangerous. I nearly caught up with Fred as I reached the top of the medial moraine, but he decided on a more direct descent down the glacier while I took the more roundabout way along the top of the moraine. I would catch up with him again past the glacier when he pause to empty snow and debris from his shoes. Further down the route, the two of us came upon Sean K above Finger Lake. I struck up a short conversation with the 16yr-old, knowing he had been eager and nervous to climb the peak which would be his hardest ascent to date. I asked him if he thought it was easier or harder than he expected. He replied enthusiastically, “Oh! Twenty million times easier!” He would be one to watch out for in future Challenges. We descended to Finger Lake where Sean K paused while Fred and I continued down. It would take us most of the next two hours to make our way back down (yet another version of) the shortcut to the Brainerd Lake Trail and then back down the South Fork drainage to the TH.

We were the first to arrive at the parking lot with Sean R only a few minutes behind us. I headed off to Independence where I had reserved a room at Ray’s Den for the next few nights. I was relieved to be done with the hardest of this year’s peaks, knowing the next two days should be considerably easier.

The only change in jersey status today was Zee reaching his 5th Challenge Peak to tie him with Emma for the lead in the White Jersey (under 25yrs). She had left after the fifth day, expecting to be done, but had decided to come back for the last two days, keeping Zee on his toes.

Nameless Pyramid

Sat, Aug 15, 2020

Day 9 of the Sierra Challenge

The oxymoron that is Nameless Pyramid lies atop the Sierra Crest a short distance south of Kearsarge Pass. I’ve gone by it on more than a dozen occasions while heading to any of a number of other summits in the area, often pausing to think, “I should climb that thing.” What had kept me from doing it previously was the stiff rating of its exposed summit block – class 5.7x, where the “X” refers to the unprotectable nature of the ascent up the narrow, 45-degree granite fin. Tom Grundy had soloed it three years earlier during the Challenge and described it in nervous terms that contributed greatly to my apprehension. But it did have a bolt up top that he thought might help to set up a top rope and allow some degree of protection, even if mostly psychological. Because it is only about 30ft high and the approach is quite short, we didn’t expect to have much difficultly getting it done in a reasonable time even if we had a large group. Tom graciously accepted the role of climbing manager for the day, choosing the gear, setting up the top rope, and managing a dozen folks up the short pitch. Additionally, JD was finishing the SPS list today. Originally, it was planned to be on Tinemaha, but that area was closed until the end of the year due to a fire. So it was moved to University Peak, a summit we’d already done on a previous Challenge, but was conveniently (or not so conveniently, as we came to find out) near Nameless Pyramid. The idea was to finish up with the Challenge peak as soon as possible, then head to University.

The obvious route is to take the Kearsarge Pass Trail from Onion Valley, then follow the ridge south to the base of Nameless Pyramid. Secor rates the ridge as class 3, and most of the participants followed this route. From the satellite view, I had spied a chute southwest of Big Pothole Lake that might shortcut the Kearsarge Pass route. I had described this option in the online description for the day’s peak, but it seems I was the only interested, or curious enough to try it. Even with some tedious boulder-hopping to get around the lake, the route worked quite nicely, enabling me to beat everyone to the point on the ridge at the top of this east-facing chute. It was not a huge lead, however, as Fred and Clement both caught up to me rather quickly and were soon ahead for the last 20min it would take to reach the base of the summit block. Robert and Grant were the first to reach the peak well before everyone else, having ascended from the east via Heart Lake. Robert soloed up and down without a rope before anyone else had gotten there (described later as “not the smartest thing I’ve done”) and went off to Snow Crown, another summit to the south on the crest. Confused, Grant went after Robert towards Snow Crown, thinking it was Nameless Pyramid. They were both gone before anyone else arrived. It was 8:30a before I had reached the peak and would take another 30min or so for the rest of the large crew to gather there.

Trailing a rope, Tom G climbed up the north side of the granite fin, then set up a top rope utilizing the old bolt on top with some additional backup. Chris then lowered him off the east side of the summit block, and we were soon ready for the production line. With various folks sharing belay duty, one by one the group made the ascent up the north side. There would be little protection were one to fall off either side of the fin, so the best Tom G could instruct was to straddle the fin should one fall or slip. Most of the climb is straightforward, but there’s about a 3-foot section 2/3 of the way up where it’s steepest and a little slippery, and it was here that the real action takes place. There was much hesitating and cursing here by almost everyone. JD went first so that he could get on with the business of his list finish by heading to University by way of Snow Crown. He was followed by Chris and Fred. Fred struggled at the crux, choosing to climb on his knees rather than trust his shoes and had some blood-letting to show for it. He was the only one to leave a bit of himself on the rock today. Sean R, Mason, Emma, Iris and Sean C went up in turn. After descending, I had each of them sign a register I would place on the summit when I went up. Because there were no stones on top with which to shelter the register, we asked each person to carry a rock up with them. Most of these turned out to be the size of golf balls, not terribly helpful, but there were enough to cobble something together. I was second-to-last, finding it about as spicy as the others had indicated, though it took less than a minute of actual work to reach the summit. I left the register under the pile of newly acquired rocks, took a photo looking off the rappel side, then went down. Tom B went last, only because he hadn’t brought rock shoes and needed to borrow mine. Tom G went back up a second time at the end to collect the gear he’d used to back up the bolt before rapping back down. It was almost noon by the time we had packed all the gear away. A handful of folks had already gone after JD to University, but those of us still at Nameless Pyramid decided it looked like too much work – we would go back to Onion Valley to wait for JD and the gang and celebrate his list finish there.

There is an interesting series of ledges and ramps on the northwest side of the crest that I had used to reach the summit block, possibly the easiest way to reach it from the crest to the north. I led six of us down this 60-foot section that someone likened to a video game. We then continued north along the west side of the crest to the top of the chute I had used and descended that. After this, our group split up as we went about finding various ways around Big Pothole Lake and back to the trail. Tom B stayed high above the lake on the south side and reported easy sailing. Sean R and I stopped on either end of the lake for a swim before catching up with the others in the boulders and on the trail. Tom would get back 10min before the next group that included Sean, Mason and myself. Tom G and Iris would be an hour later still, stopping to take a couple of swims at the lower lakes.

Back by 2p, we settled in for a relaxing afternoon under Tom’s pull-out shade on the side of his Jeep. Adult beverages and salty snacks were consumed over the course of the afternoon. Clouds had built up threatening rain, but only a few sprinkles ever materialized. JD and the others from University didn’t return until 6p, by which time the rest of us were relaxed and feeling little pain. JD became only the third person to day hike the SPS list, ten years after the Matthew and I had done it in 2009 and 2010, respectively. Well done, JD!

For the first time in eight days, Fred was not first to return. Sean C got the stage win, though partially by accident. We had let him be one of the first to go up and back down so that he could return to Kearsarge Pass where his wife was waiting with their infant son. The plan was for Asaka to then scramble from the pass to Nameless Pyramid and take her turn. She didn’t like the look of the ridge as a soloing exercise and declined. Fred ended up half an hour behind Sean C and an hour ahead of the next person. Meanwhile, Clement went off to Snow Crown, Rixford, Falcor and Mt. Gould in a wide tour around Kearsarge Pass. Not to be outdone, Grant did all those plus Glacier Spike and six of the Kearsarge Pinnacles. Once he realized he had missed Nameless Pyramid, Grant planned to revisit it at the end of the day to solo it as Tom G and Robert had done previously. Unfortunately, later afternoon rain had left the rocks wet and he deemed that an unsafe risk. It was the only Challenge peak he would miss from this year’s list. Emma and Zee remained tied for the White Jersey with six Challenge peaks each.

Mt. Fitch

Sun, Aug 16, 2020

Day 10 of the Sierra Challenge